Writing successful proposals and grants

Published: 23 January 2025

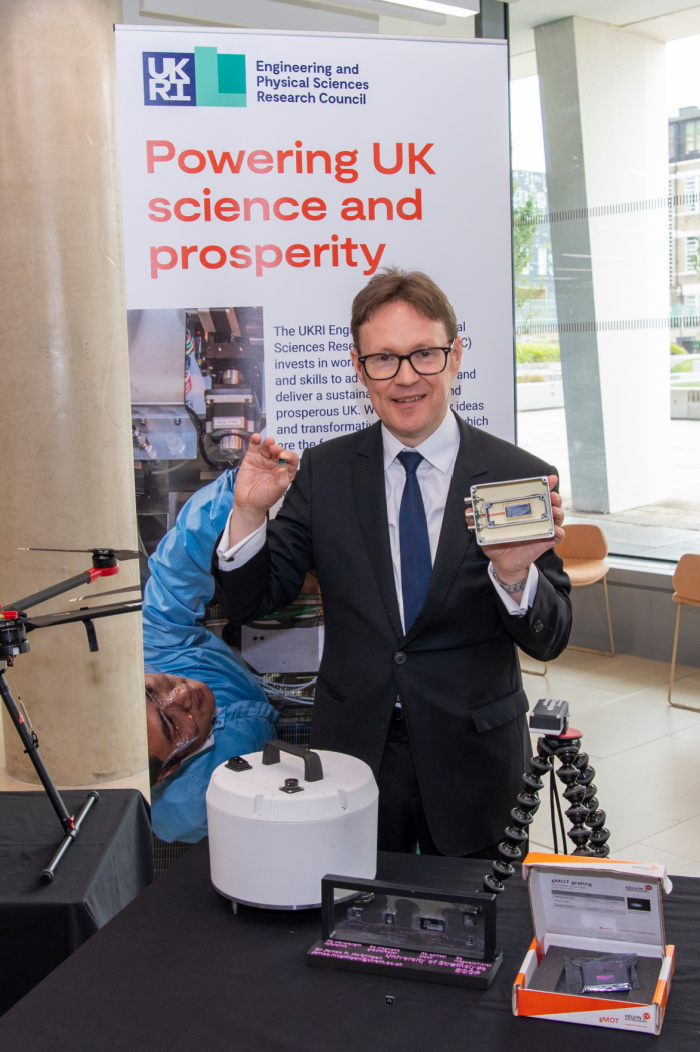

Professor Doug Paul discusses his funding journey in a growing field of research.

Professor Douglas Paul, Principal Investigator of the £22 million QEPNT Hub discusses how serving on panels improved his bid performance in Research Professional.

Doug, Professor of semiconductor devices at the University of Glasgow and principal investigator for the UK Hub for Quantum Enabled Position, Navigation and Timing, is a busy man. At present, he’s in a leadership position for nine research projects and programmes.

Among his many awards, he holds fellowships at the Institute of Physics and the Royal Society of Edinburgh, as well as a research chair in emerging technologies from the Royal Academy of Engineering. And he was recently awarded an OBE for his services to quantum technology research.

Here, he discusses his funding journey to the top in a growing field of research.

How did your first proposals go?

After my contract as a postdoc at Cambridge, there was essentially no more funding, so I was given three successful proposals and I was basically told to go and write something myself. The first three proposals I wrote all got funded. The next two I wrote didn’t, but the typical statistics are that if you want a guarantee for funding, write three grants, expecting you might get funded for one.

What did you learn from those early grants, both the failures and the successes?

What I’ve seen over my career is there could be times where you’re too early in a topic and you won’t get funded because it’s brand new, and peer review is not actually good at high-risk, new things. But persistence works. I often tell early career researchers about this one proposal I co-authored that was in a very new area, and peer review crucified it, telling us it was never going to work, no way would it attract funding. But we did get just enough for a PhD student, who managed to get a patent, and we’ve now had over £6 million worth of funding, including £2m in cash from companies interested in the tech.

What else do you tell early career researchers regarding grants?

Sitting on a lot of panels has really helped me understand how to get things funded. On panels and when refereeing bids, you see other people’s proposals and you learn better ways of presenting ideas—and you learn what doesn’t work. I tell early career researchers that when you get the chance to referee proposals, do it. And when you do, make sure to take note of where people have written things that are much better than you would have and look at how you can improve.

What did you learn as a referee?

Well, early career researchers have more time to write relative to senior researchers, and younger researchers don’t tend to understand that seniors will only have a very short period of time to referee a proposal. The other bit they don’t tend to incorporate into their writing is that most proposals will not be refereed by a technical domain expert—that’s mostly been my case. I’m a scientist who can understand enough to judge if something is good or bad, or is likely to work. But a lot of referees won’t understand specific technical details. You’ve got to try to make sure that in the opening paragraphs, you explain well why your proposed work is important and why it should be funded.

How did the bid for the quantum positioning hub come together?

Glasgow had a previous quantum hub; it’s had two phases now. The first was the quantum imaging and sensing hub, which was due to conclude in 2024, so in January 2022 my Head of College brought all the seniors together and the then lead for the hub didn’t want to continue in that role—it’s a lot of work over 10 years. So they went round the table and everyone pointed at me.

But a month after that meeting, I had an interview for an £11m programme grant. So I said I’d get started on the hub the day after that interview. And I did. I started with a blank sheet of paper, and by the end of the day I’d worked out who I was going to invite on board as investigators. I made sure nearly half of them were early career researchers, so it wasn’t just senior researchers from a particular university with the right skill set. I wanted to make sure that we could help train the next generation there too. And it’s been incredible; the enthusiasm and the energy from those researchers has been fantastic.

How much funding have you managed to get on that project?

We’ve ended up with around £22m worth of funding. There’s a lot of governance and oversight to make sure you’re spending it wisely, because it’s taxpayer money, of course. That’s one of the other things I’m always thinking about when refereeing, because I’m a taxpayer as well. Would a taxpayer like that grant to be funded? Could the principal investigator justify to any taxpayer why it should be?

What’s something that hasn’t been covered by a project you’ve worked on that perhaps you still think about?

I’m always coming up with new ideas for research. I think if anything, the one thing that would be nice in the UK grant system is more mixed proposals involving academia and industry. The US is quite good at that, of course, with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

I’ll often go and talk with end users first when I have ideas and find out what they need and where the demand is. It’s important to try to fill those challenges the end users have. You’re delivering something useful and strengthening your proposal by saying there’s a market for this. We have students rubbing shoulders with industry in the cleanroom, but it’s important to also do the research on production tools that will make it easier to translate the technology into industry.

Top tips

- Serving on panels is invaluable experience—when you get the chance, accept it.

- When doing so, make sure you learn from sections of bids that are written better than you would have written them.

- Always consider your audience when writing bids—they will mostly be time-poor senior academics, not specialists in your field.

- Including early career researchers on projects is not just a box-ticking exercise—they will invariably bring extra energy and drive.

This article first appeared in Research Professional on 16th January 2025.

First published: 23 January 2025

<< News